On October 30, 2020 Michigan Congresswomen Rashida Tlaib and Alexandra Ocasia Cortez introduced legislation that would facilitate the creation of state and locally administered public banks: the Public Banking Act,. Public banks are socially-minded financial institutions, and operate with fair practices while prioritizing public access over profit. In lieu of highly-compensated executives and Wall Street middlemen, public banks offer lower debt costs to city and state governments, fund public infrastructure projects, and provide low-interest loans to small businesses and under-banked individuals. Prohibited from investing in fossil fuels, public banks can also increase ecological health by financing renewable energy.

The need for socially-conscious banking institutions is greater than ever.

The need for socially-conscious banking institutions is greater than ever.

America’s current financial system

has deprived over 55 million Americans access to basic financial services via unaccessible capital and predatory lending, leaving the most at-risk individuals vulnerable to a deluge of deregulated predatory cash-advance stores. A 2020 study by the National Community Reinvestment Corporation found that Black business owners were less likely to receive bank-administered coronavirus financial aid through the Paycheck Protection Program than their white counterparts. In 2013 Goldman Sachs was discovered to be manipulating commodity prices by routinely moving massive caches of aluminum ingots between 27 Detroit-based warehouses, a practice that delayed legitimate orders and passed the increased price of aluminum onto consumers. Time and again existing financial institutions have proven their inability to address structural racism, systemic corruption and environmental injustice.

Although the concept has been met with skepticism, there is one public bank precedent that has been successfully serving its community for more than a century. The state-owned Bank of North Dakota was established in 1919 to neutralize local farmers' dependence on out-of-state financial institutions which frequently took advantage of them. As a sparsely populated, decentralized agricultural state without a robust banking economy, farmers in North Dakota were vulnerable to predatory lending and the undercutting of grain prices by financial capitals in Chicago and Minneapolis.

Seeking to redress the state’s status as a banking desert, the Depression-era Non Partisan League, a populist progressive political party, won state-wide offices by convincing voters of the merits of state-owned banks and agricultural apparatuses like mills and elevators. This socialist-minded civic infrastructure is still in place today and acts as an economic incubator within a deeply conservative red state. The newly-introduced Public Banking Act legislation builds off Bank of North Dakota’s example by subverting the capitalist system in order to represent the needs of local communities.

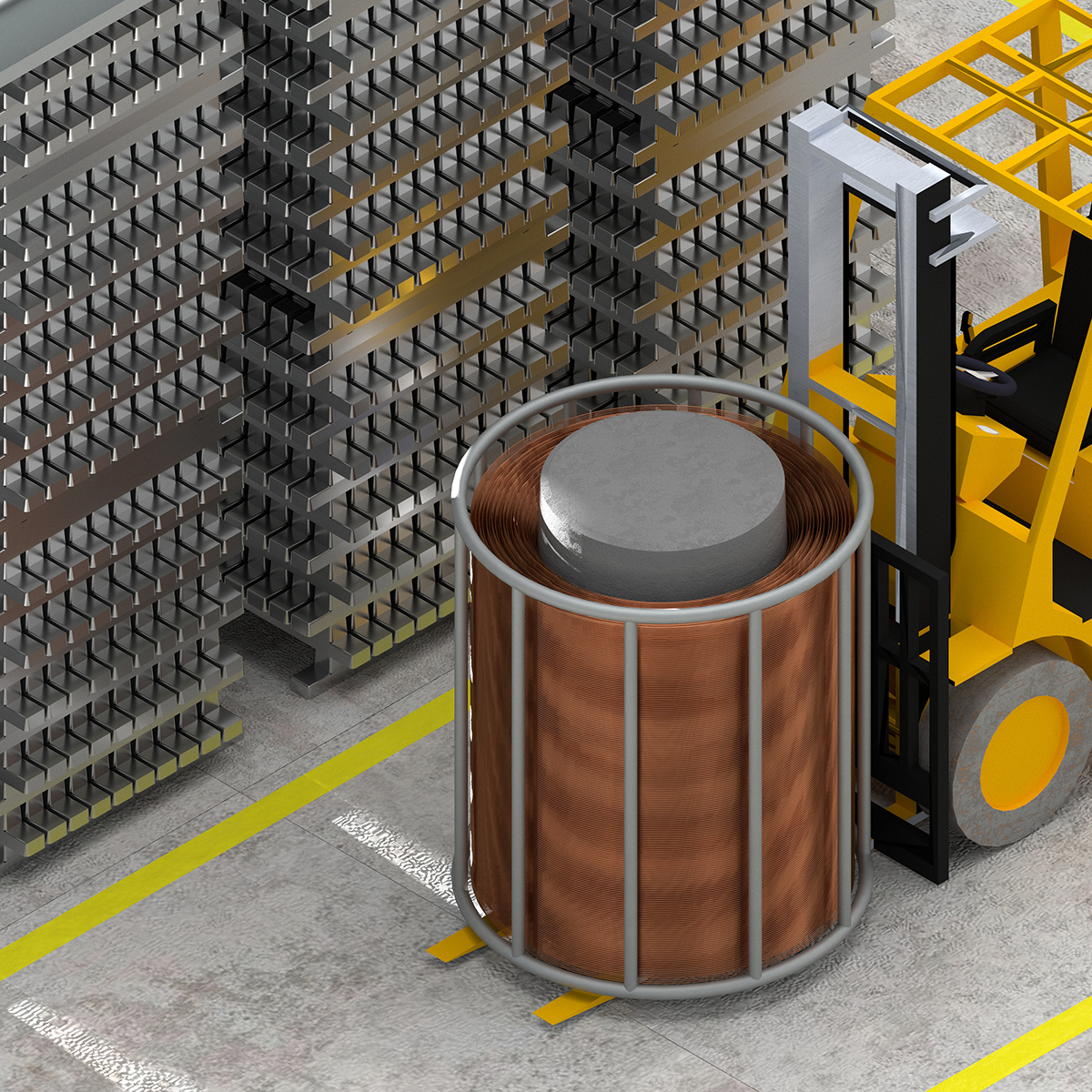

The design proposition materializes this new civic infrastructure by combining elements from two existing building typologies in order to produce a new spatial scenario. The “American Vernacular Barn,” rooted in the history of public banks through its affiliation with the Bank of North Dakota, provides an element of social representation through the iconic red and geometric quilt squares that adorn many family barns. The “Industrial Warehouse,” a facility for commodity storage and economic fulfillment, informs the project’s spatial logic and uniform envelope.

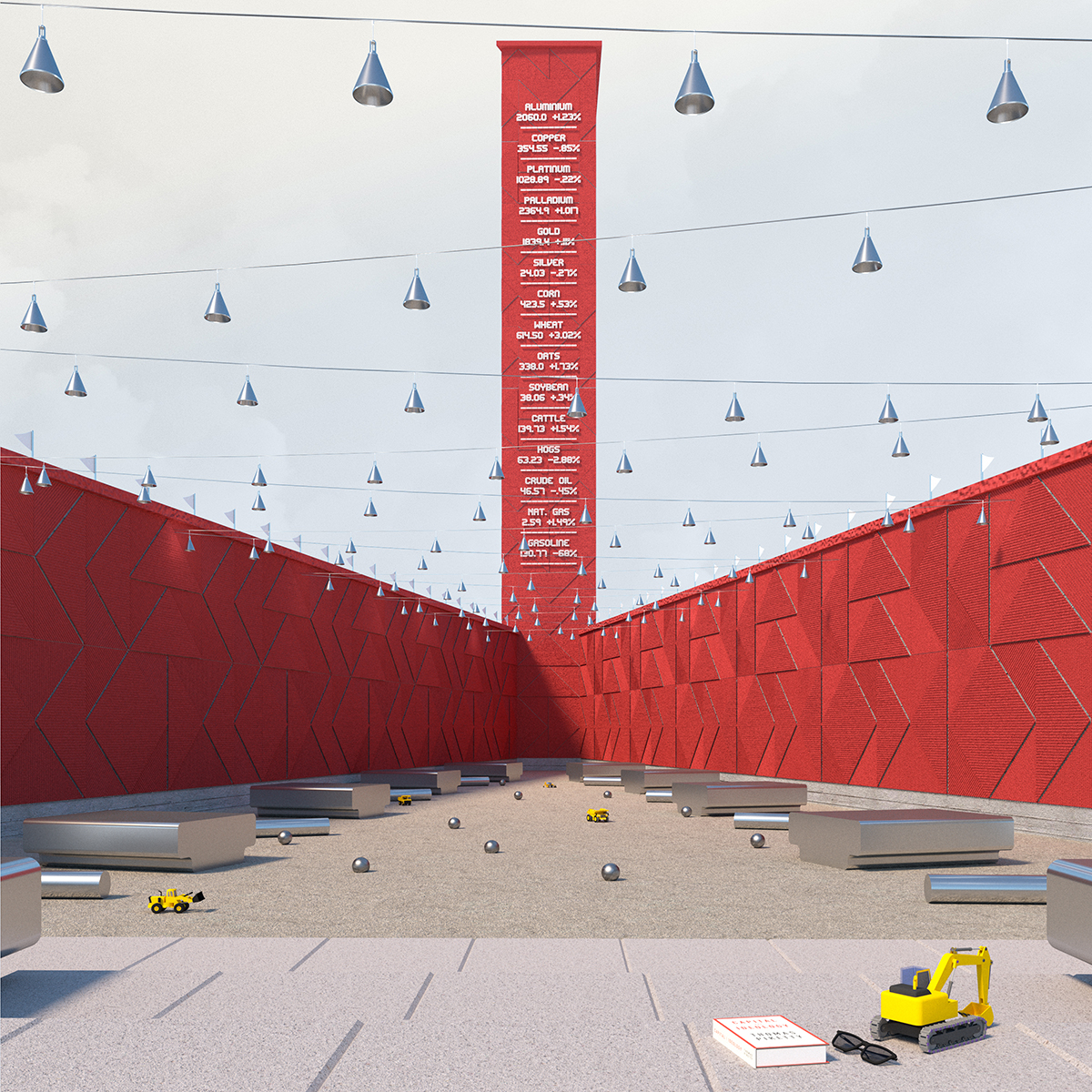

Behind the public bank’s totalizing facade lies an interiority of different scales, where buildings within the building fulfill the bank’s programmatic diversity. The triangular floor plan is defined by the tension inherent in acute angles - between the needs for efficiency of space and the radical will of geometry. Orthogonally divided by program and bisected by a thru street, the mass is organized around the central commodities warehouse, with public-facing bank, corporate offices and secure delivery dock adjacent to this central square. The triangle’s vertex contains the bank’s spatial loan program, where micro-retail units incubate small businesses and courtyard parks provide public space.

Committed to adding transparency to banking, the public bank manifests its investment portfolio, making it visible to the public both in its lobby and outdoor spaces. The courtyard represents a spatial gift to the public, where the friction between public and private interests can be mediated. Raw commodities become playthings and the day’s trading exchange values adorn the building’s apex watchtower, which functions as a lookout for capitalist encroachment.

Amassing its own inventory of raw commodities, the public bank acts as a defense against Wall Street’s speculative stockpiling, while also providing local infrastructure projects with a reliable and below-market rate supply chain. Ceiling height stacks of industrial metals like aluminum ingots, steel tubing and copper coils surround a central vault where precious, rare-earth elements are securely stored.

FALL 202O INSTITUTIONS STUDIO

INSTRUCTOR: EDUARDO MEDIERO

PROJECT BY: PRESCOTT TRUDEAU

TAUBMAN COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN